I, for one, have sworn, by the sword of God that has struck us, and before the beautiful face of the dead, that the first joke that occurred to me I would make, the first nonsense poem I thought of I would write, that I would begin again at once with a heavy heart at times, as to other duties, to the duty of being perfectly silly, perfectly trivial, and as far as possible, perfectly amusing. I have sworn that Gertrude should not feel, wherever she is, that the comedy has gone out of our theater.I understand this, and even more I feel understood by this. We honor the dead, we honor the living, we even honor life and the giver of it, by whatever lightness we can muster. That doesn't excuse us from fighting for the good, from taking the wrong and the evil and the destructive to task. But it does set a tone for life that is itself life-giving.

Tuesday, January 28, 2014

The First Joke That Occurred to Me

For the young male evangelical would-be writer--maybe further differentiated by a quality of unmasculine whimsy and melancholy--there is a standard progression: starting with C. S. Lewis, of course, and then proceeding to Frederick Buechner and eventually arriving at G. K. Chesterton. There are other luminaries along the way, and not every young male evangelical would-be writer's path is identical to all the others, but I feel confident that these three are common touchpoints for all of us-I-mean-them.

This has certainly been the case for me, at least. I did my duty with Lewis, reading a couple of short books by him (including only a few of the Chronicles of Narnia, I confess) before falling hard for Buechner--his soulful, mournful essays, his pithy, incisive insights. I stole some writing tics from him for a while before I realized that it did him no good and made me sound pretentious. But I soon thereafter landed at Chesterton, and I never really left.

Something about Chesterton grabbed me right away. I realized quite quickly that he started and ended every thought with a laugh. After the prim propriety of Lewis and the sad sobriety of Buechner, I was more than ready for that. And yet that lightness in Chesterton didn't translate into a superficiality or vanity that so often characterizes humor, and neither did it descend into cynicism and scornfulness as does so much humor of my own time. Chesterton took on his intellectual opponents with gloves off, and he pegged them square on the nose with every shot, but those hits were delivered as punches on the arm, slaps on the back: they were predicated on love and received as affection. The people he debated felt appreciated and understood, the world he described for his readers was rendered both more relatable and more ineffable.

I find that humor is rarely given its due. No Oscars for Bill Murray, for example, and a film about Batman or the Terminator is more likely to earn a best picture nod than a film about fundamental absurdities. And yet worlds are conquered, tyrants deposed, wounds are healed less often by vigilantes and apocalypses and far more often by way of a good laugh. Chesterton understood that, and that gives me hope.

I'm reading about Chesterton in Buechner's Speak What We Feel, Not What We Ought to Say, which means that Chesterton's lightness is getting a bit of the heavy treatment. But I think that's a good thing: until honor is bestowed by the sober-minded, a clown remains only a clown. By placing Chesterton (and fellow wit Mark Twain) alongside Shakespeare and Gerard Manley Hopkins, Buechner reminds us that you don't have to be dour to be brilliant. Buechner quotes at length a letter from Chesterton to the woman who would become his wife after the death of her sister:

Friday, January 24, 2014

Farewell to a Paradigm Shift

A first pet is a paradigm shift. Once you bind yourself to a pet, you see the world differently.

A pet extends your empathy beyond human relationships; you begin to give thought to how your actions, your decisions, even your mood affect another creature who can never say they love you, they need you, they trust you. A pet will never be enculturated into a common human experience, and yet a relationship with a pet extends over decades, conducted always in the sacred shared space of the home. Pets are like God in that they are utterly other, and yet they are as near to us as the air we breathe, and in the deepest part of us we long to know them and be known by them.

Lucy was my paradigm shift. Only after we welcomed her into our home did I learn that closets could be hiding places, that boxes could be beds, that tabletops could be temptations. I learned to recognize the subtle variations in purrs and mews as carrying distinct meaning. I fed her, cleaned up after her, saw to her needs, struggled to correct her bad behavior and reveled in her moments of remarkable serenity. I learned to be more humane, more human, by being in relationship with her.

Lucy was a paradigm shift. This afternoon we said goodbye to her. She changed us just by being with us; we see the world differently since Lucy entered our lives. I am a different person because of Lucy, and I'm better for it, and I thank her for it.

Monday, January 20, 2014

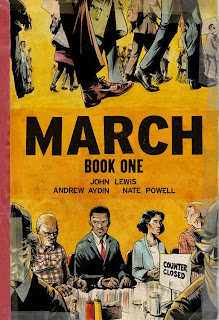

I Like MLK More Than MLK Would Like Me

Every year on Martin Luther King Day I read a letter to white clergy that he wrote while imprisoned in a Birmingham, Alabama jail. I read it for its historical significance; last April it turned fifty years old, and it was followed in King's canon a few months later by his "I Have a Dream" speech during the 1963 March on Washington. The letter marks a pivot point; King was no longer ignorable to the national white majority, and meanwhile the Civil Rights Movement itself was beginning to lose patience.

You see hints of that percolating impatience in the letter, written in response to a letter from white clergy criticizing the methods of King and his colleagues as disruptive and agitating. You can taste King's frustration in his letter--I imagine earlier drafts whose sarcasm and accusation are given their visceral vent, before King wisely considered that he wasn't writing only for these short-sighted and weak-willed clergy but for history. I imagine him yelling, even punching the wall of his cell, before eventually composing and editing himself.

When I imagine the letter in this way, my eyes begin to compensate, and I begin to see myself not in the people King praises (people like Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill, who I'm proud to say is my wife's great-uncle) but rather in the people King reproves.

I like love. Some days I even love love. Having not lived in the 1960s, I have a somewhat fantastical nostalgia for the Summer of Love and the ethos of love that I paint on the era. In my imagined history, everyone is MLK or Bobby Kennedy or John Lennon or even anachronistic exemplars like Gandhi and Jesus. Set against them are a very few nefarious, mustache-twisting, love-hating villains like Bull Connor and the like. In my imagined history, I side unswervingly with the Kings, the Kennedys, the love people. In my mind I'm on the right side of history.

But history is never so neat. When I'm honest with myself, I easily imagine myself doing nothing or saying nothing in the face of racial inequality. Even worse, I imagine myself resenting the movement for civil rights as it disrupts my precious status quo, as it presses against the privilege I enjoy as a white man of reasonable means, as it makes my day-to-day existence slightly less comfortable, as it forces me to acknowledge the reality of racial violence and systemic injustice. When I'm honest with myself, I hear King's frustration pointed at me.

Having ears to hear, however, is a good thing. Even as it problematizes the present, it makes a better future possible, even inevitable. So today I'll reflect on King's more confrontational passages from his Birmingham letter, and I'll invite God to confront me where I make other people wait for rights that I enjoy without cost, to shake me out of whatever appalling silence I'm indulging and back onto whatever right side of history I've wandered off.

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, "Wait." But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can't go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: "Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?"; when you take a cross county drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading "white" and "colored"; when your first name becomes "nigger," your middle name becomes "boy" (however old you are) and your last name becomes "John," and your wife and mother are never given the respected title "Mrs."; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of "nobodiness"--then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. ... I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season." Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection. ... We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.*** In case you missed it over the weekend, I posted a video of Peter Gabriel singing "Wallflower," his profound and achingly beautiful tribute to people whose refusal to wait for justice causes them to suffer. You can watch the video here.

Thursday, January 16, 2014

Let Your Spirit Be Unbroken

I was in a meeting today where someone shared the story behind Vincent Van Gogh's Mulberry Tree. He painted it while institutionalized; apparently the vividness of his painting was his own imagination, since he was hospitalized during the late fall.

The story reminded me of a song I listened to over and over and over again while I was in college: "Wallflower" by Peter Gabriel. I was under the mistaken impression back then that it was a song about his own time in an asylum, when in fact it's a tribute to the political prisoners of South Africa and other tyrannous governments back in the 1970s when he wrote it. Whatever it was about, I felt understood by it. I was a bit self-pitying back then.

Anyway, the song still holds up, and perhaps you'll feel understood by it today, whether your sense of oppression is political or professional or psychological or spiritual. It's a bit early for a Martin Luther King Day post, but this song would certainly could have been sung to him.

Friday, January 03, 2014

Time in Sounds, Shadows and Scents

Maybe it's the beginning of a new year; maybe it's the looming milestone birthday of my mother or the retirement of the coworker who hired me sixteen and a half years ago. Maybe it's just force of habit. But I've been thinking a lot recently about the passage of time.

I've always had a thing for time. Kind of a love-hate thing, I suppose: I lie awake some nights anxious over what it will be like to be seventy, but I can't help myself when I stumble across stuff that deals with time as a concept. My first posts to Loud Time, for example, were three installments of "A Prayer About Time" by Australian theologian Robert Banks (here, here and here). Here's a little taste of that poem:

God our Father, you are not so much timeless as timeful, you do not live above time so much as hold "all times . . . in your hand", you have prepared for us a time when we will have leisure to enjoy each other and you to the full, and we thank you, appreciate you and applaud you for it.Right now my time-obsession is being enabled by Robert Levine's book A Geography of Time: The Temporal Misadventures of a Social Psychologist, or How Every Culture Keeps Time Just a Little Bit Differently. The book is nearly twenty years old, which makes it a bit quaint--it's always interesting to read social psychology or other social-scientific inquiry from a bygone era, and this particular bygone era doesn't take into consideration the fact that most of us have replaced wristwatches and wall clocks with smartphones and tablets. (Seriously: so far he hasn't even mentioned the Internet.) But I'm really liking his historical content, which sets up nicely the contrast between Western-industrial age conceptions of time and non-Western equivalents. For one thing, whereas we Westerners perceive time as something objective, authoritative and, I don't know, looming, other cultures have a more tactile, almost sensual appreciation of time. As just a few examples:

The Chinese developed an incense clock. This wooden device consisted of a series of connected small samesized boxes. Each box held a different fragrance of incense. By knowing the time it took for a box to burn its supply, and the order in which the scents burned, observers could recognize the time of day by the smell in the air.Not to be outdone are the Natives of the Andaman jungle in India, who "have constructed a complex annual calendar built around the sequence of dominant smells of trees and flowers in their environment. When they want to check the time of year, the Andamanese simply smell the odors outside their door." The sundial manipulated sunlight to track shadows over the course of a day, "while water clocks [slowly dripping water from one bowl to another] marked the hours of night." This was the way of the Western world "for most of recorded history," until the invention of the mechanical clock, designed

to simply sound bells at the appointed prayer hours. Most of these early clocks, which became community centerpieces, didn't even have hands or hours marked on their faces. They were designed not so much to show the time as to sound it.Sounds, shadows and scents. I like that. For most of our history time was more servant than master, more companion than overlord. Levine suggests that until we began imagining ourselves accountable to time, rather than occupiers of it, the word speed didn't exist. "For most of human civilization there was no way to insure being punctual even if one wanted to be." That's certainly no longer the case. Time stares us in the face these days; it confronts us at every turn, with the cold stare of a sans serif font or the magisterial conceit of roman numerals. The only sound time offers us anymore is not the organic drip or the resonant gong but the steady march of what Harlan Ellison calls "the Ticktockman" and the occasional ping of our iCalendars. Time has ceased to be organic; it's been outsourced to the technological powers that be. I'll surely write more about this book. But for now I'll leave you with a more recent lament--one that, ironically enough, I always enjoy hearing.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Both Inspiration and Cautionary Tale: Excerpts from Middling

What follows is an excerpt from the Winter 2021 edition of Middling, my quarterly newsletter on music, books, work, and getting older. I...

-

I've recently begun reading the collected novels and short stories of Sherlock Holmes as written by Arthur Conan Doyle. I'm a trend-...

-

I've been moving slowly through How Music Works, the colossal tome by Talking Heads frontman David Byrne, over the past few months. My ...

.JPG)